Babesia

Introduction

Babesia Starcovici, 1893

Type species Babesia bovis (Babes, 1888) Starcovici, 1893

The genus Babesia is one of the most important representatives of the piroplasmids and has a substantial impact on both the veterinary and medical communities. It has always been assumed that Babesia species are highly adapted to specific vertebrate hosts, but some recent observations are in disagreement with that. The relatively low host specifity is probably the reason why some species (Babesia microti, B. divergens, and newly described B. duncani) occassionally infect even man.

In 1893, Smith and Kilbourne discovered that Babesia bigemina, a causative agent of bovine babesiosis, is transmitted by the tick Boophilus annulatus. This revelation was a breakthrough in the history of parasitology, as it was the first proof that an arthropod was the vector of any disease agent.

Characteristics

Ticks from several genera are now known to be vectors and reservoirs of numerous Babesia spp. transmissible to an array of mammals. Trophozoites multiply in erythrocytes by binary fission forming pairs, or by merogony forming tetrads. Filaments are not present on parasitized erythrocytes (compare with the genus Echinozoon). Vertebrate hosts are mammals and birds, ticks serve as vectors.

The genus presently contains more than 120 species, often with a worldwide distribution, that usually infect mammals such as bovines (B. argentina, B. berbara, B. bigemina, B. bovis, B. divergens, and B. major), small ruminants such as sheep and goats (B. foliate, B. ovis, B. motasi, B. crassa, and B. taylori), horses and donkeys (B. caballi and B. equi recently transferred into the genus Theileria), pigs (B. perronciti, B. trautmanni), dogs (‘large Babesia’ B. canis and ‘small Babesia’ Babesia (or ‘Theileria’) gibsoni), cats and other felids (B. herpailuri, B. panthera, and B. felis with unclear position and names as Theileria felis or Cytauxzoon felis) and rodents (the Babesia microti group). Humans can also be accidentally infected with several species (mostly B. divergens or B. microti of rodents). Human babesiosis occurs mainly in the New World where it is a serious disease, especially in immunocompromised and splenectomized persons.

The validity of 14 species of avian piroplasms of the genus Babesia was recognized. All species of avian Babesia are characterized by the presence of fan-shaped or cruciform tetrad schizonts presenting the characteristic ‘Maltese cross’ formation. Most species of Babesia infecting mammals or birds are host-specific at least to the family level. While the majority of species infecting domestic mammals cause disease, only one avian species, B. shortti, is known to be pathogenic.

List of valid avian species of the genus Babesia according to Peirce

- Babesia ardeae Toumanoff, 1940

- Babesia balearicae (Peirce, 1973) Peirce, 1975

- Babesia bennetti Merino, 1998

- Babesia emberizica (Yakunin and Krivkova, 1971) Peirce, 1975

- Babesia frugilegica (Yakunin and Krivkova, 1971) Peirce, 1975

- Babesia kazachstanica (Yakunin and Krivkova, 1971) Peirce, 1975

- Babesia kiwiensis Peirce, Jakob-Hoff and Twentyman, 2003

- Babesia krylovi (Yakunin and Krivkova, 1971) Peirce, 1975

- Babesia moshkovskii (Schurenkova, 1938) Laird and Lari, 1957

- Babesia mujunkumica (Yakunin and Krivkova, 1971) Peirce, 1975

- Babesia peircei Earlé, Huchzermeyer, Bennett and Brossy, 1993

- Babesia poelea Work and Rameyer, 1997

- Babesia rustica (Yakunin and Krivkova, 1971) Peirce, 1975

- Babesia shortti (Mohammed, 1958) Corradetti and Scanga, 1964

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

The classical difference between the genera Theileria and Babesia is the absence of the extra-erythrocytic asexual multiplication (schizogony) in Babesia, while schizogony in Theileria occurs in the lymph nodes and erythrocytes rather than in the erythrocytes alone. Another typical feature is the parasite cycle in the vector tick, which includes transovarial transmission in Babesia but only transstadial transmission in Theileria. Moreover, the multiplication in the red blood cells results in two daughter cells (merozoites) in Babesia, while four merozoites (Maltese cross) are formed in Theileria.

Despite such a clear distinction, systematic affiliations of several species of piroplasms, even those with economic impact, remain unresolved. Small piroplasms of equines are still associated with Babesia, although they in fact belong to Theileria. Two species of piroplasms are described in equids, Babesia caballi and Babesia equi. They were later transferred into the genus Theileria based on the characteristics of the life cycle and phylogenetic analysis.

Even more complicated is the situation with Babesia microti. It has schizogony in lymphocytes and its development and transmission in ticks are more similar to the genus Theileria. For that reason, it is now referred to as Theileria microti. On the other hand, molecular evidence indicates that these parasites differ from both Theileria and Babesia. As in other apicomplexan groups, molecular tools are becoming increasingly important for phylogeny reconstruction within the order Piroplasmida.

In the last years, some new species (like Babesia leo, B. venatorum, or B. bicornis) have been discovered using classical morphology-based methods. At the same time, other species emerge from within well-known species based on molecular methods. For example three “groups” of canine B. canis differentiate in vector specificity and pathogenicity and therefore, three biologically (and immunologically) defined subspecies have been described: – B. canis canis transmitted by ticks of the genus Dermacentor (mainly in Europe); B. canis vogeli transmitted by Rhipicephalus ticks (in southern Europe and northern Africa); and B. canis rossi transmitted by Haemaphysalis ticks (in South Africa). Likewise B. gibsoni was recently subdivided into three strains ‘Asia’, ‘California’, and a recently described Theileria annae. Another typical example is Babesia microti, which has historically been considered a common parasite of Holarctic rodents. However, human babesiosis due to this species has generally been limited to America and the absence of reports of B. microti human babesiosis from other sites where the agent is enzootic (e.g., in Europe) remains unexplained. Based on DNA analysis it was demonstrated that ‘B. microti’ is a species complex with three distinct clades including even parasites from non-rodent hosts. The level of genetic divergence detected in piroplasmids has led us to suggest that new subspecies (or even cryptic species) might be found within these parasites, although no specific names have yet been proposed.

Title Illustrations

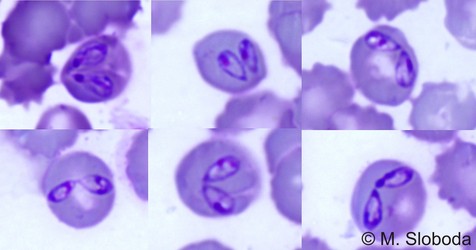

| Scientific Name | Babesia canis |

|---|---|

| Location | Parasites in dog's blood |

| Identified By | M. Sloboda |

| Image Use |

This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0. This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0.

|

| Copyright | © 2008 |

About This Page

This page is being developed as part of the Tree of Life Web Project Protist Diversity Workshop, co-sponsored by the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR) program in Integrated Microbial Biodiversity and the Tula Foundation.

Page copyright © 2011

Page: Tree of Life

Babesia.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

Page: Tree of Life

Babesia.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

- First online 18 May 2011

- Content changed 18 May 2011

Citing this page:

Tree of Life Web Project. 2011. Babesia. Version 18 May 2011 (under construction). http://tolweb.org/Babesia/68087/2011.05.18 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site